All you need to know about girth fitting

There is a growing interest in the topic of anatomical bridles, bits, and girths, along with increased rider awareness of the importance of correct fit to meet the needs of both horse and rider. And while saddle and bridle fitting have been discussed in many publications and it seems obvious to everyone that these tack items require proper fitting to the horse (and of course the rider), less attention has been paid to the issue of adjusting the girth.

The girth, a key element of the equestrian's tack, serves primarily to hold the saddle firmly on the horse’s back. However, in order to fulfill this role well, it must be adjusted to meet the individual needs of the horse, taking into account both biomechanical issues related to the equestrian discipline (dressage girths, for example, have different shapes than those used in show jumping) as well as anatomical issues regarding the animal in question.

A correctly fitted girth can significantly improve the overall performance of the horse – it will positively impact its biomechanics, increasing the horse's freedom of movement, especially in the front limbs. Consequently, the horse will relax and lift its back more easily. Work in relaxation improves muscle condition and overall comfort of the animal.

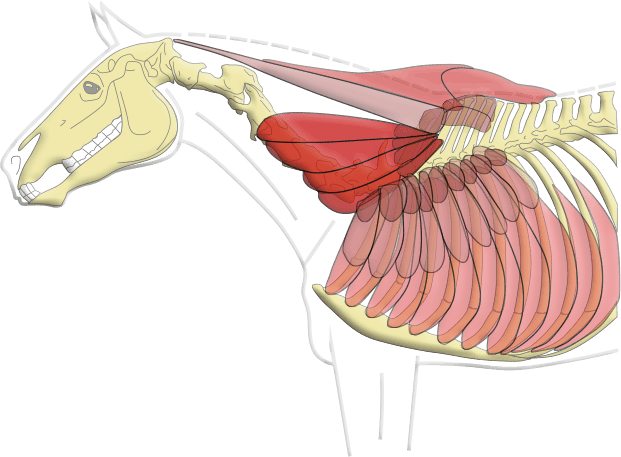

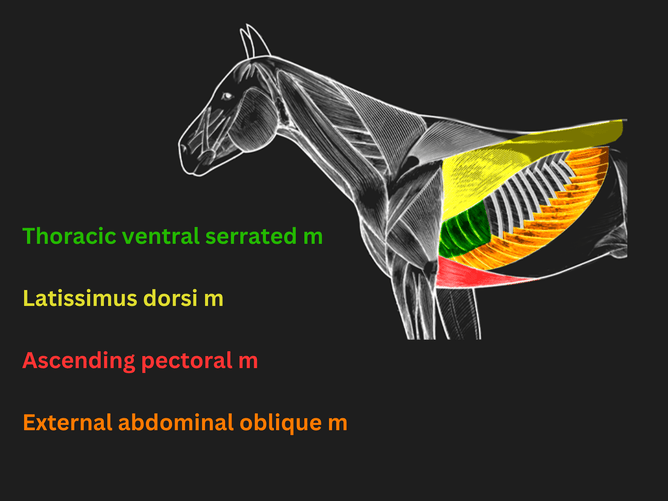

There are many important anatomical structures at the point of attachment of the girth, both bony (sternum, thorax, ribs 5–7) and myofascial (mainly muscle groups belonging to the thoracic sling and their further connections with the back and thorax). The most important ones include the cutaneous trunci muscles, the latissimus dorsi, the ascending pectoral (aka deep pectoral) muscles, and the ventral serrate muscle located in the deeper layer, under the latissimus dorsi.

Optimal cooperation of these muscles is crucial for the proper biomechanics of the horse, as it is involved in the engagement of the back and lifting of the sternum, and thus in the proper workings of the whole body in motion.

Anatomical structures related to the girthing area

SUPERFICIAL LAYER

cutaneous trunci m.

MIDDLE LAYER

latissimus dorsi m.

DEEP LAYER

serratus ventralis m.

DEEPEST LAYER

external abdominal oblique m. intercostal muscles

The sternum is one of the most innervated structures in a horse's body. It is situated near the brachial plexus, which innervates the entire pectoral limb. It is also the junction of the nerves going from the spinal cord through the cutaneous (skin) muscles and intercostal muscles, thereby innervating the chest.

One should not forget about the vital internal organs, such as the heart, lungs, and diaphragm, located exactly in the area under the girth and the optimal function of which is crucial for the horse's exercise physiology and optimal performance.

Example of symptoms related to incorrectly fitted girth

Practical example: The owner of a 5-year-old dressage mare noticed symptoms related to discomfort in the girth area of her horse and contacted me to get help with this issue. The moment the girth was attached, the mare reacted very nervously – to the extent that she began showing aggressive behavior towards the owner during saddling (biting, kicking with foreleg).

This concerned the owner, who reacted quickly and asked for help. During the initial interview, we were able to rule out other factors that could be causing the mare's behavior (e.g. gastric ulcers, unfitted saddle, mouth/teeth discomfort). The girth was indeed badly fitted – it was too short (the buckles irritated the elbow joint during retraction of the limb) and too stiff (sensitive reaction to palpation of the skin in the area behind the elbow joint). After a manual therapy session, a series of stretching exercises and a change to a longer and softer girth, the problem was successfully resolved.

If you have doubts about the correct girth fit, it is worth consulting a specialist – a saddle fitter or an equine physical therapist who can help you find a girth that's suitable for your horse and adjust it properly to the saddle.

What makes an ideal girth?

It should ensure optimal function of the nerves without putting too much pressure on them – a girth that distributes pressure evenly along the place of its attachment will work best. It is worth paying attention to the width of the girth and a flat, even surface on the medial side (the side touching the horse’s skin).

It should allow the thorax to work freely and not restrict the horse's ability to breathe freely. Girths that have elastics on both sides allow the ribcage to open freely during exertion.

It should be shaped with the horse's anatomy in mind and the type of work he is doing. For example, horses in jumping training are often given wide girths with additional protection of the sternum area (these are known as belly guards or stud guards); they not only support the sternum during a jump, but also protect it from possible injury through contact with the hooves or with fences.

It should lie well (it should not be too short, too long, crooked, not fastened properly), evenly distributing the weight of the saddle and the rider.

The material from which the girth is made is equally important. A horse's sensitive skin will react quite differently to synthetic material than it will to natural materials such as high-quality leather or wool.